Exploring the Myth of Rock ‘n’ Roll with Joan Didion and Eve Babitz

Didion and Babitz reclaim literary journalism, with the subject of Jim Morrison functioning as a compelling figure that represents the mystery of Los Angeles.

Joan Didion and Eve Babitz are two of California’s most celebrated writers, both of their identities inextricably tied to the cultural and social scenes of the state’s bygone eras of the 1960s and ‘70s. The two women ran in the same writers' circles, with artist Paul Ruscha calling Babitz “the [older] daughter Joan and John [Gregory Dunne] never had”(Los Angeles Magazine 2022). Didion is even responsible for getting Babitz published for the first time, championing an essay that appeared in Rolling Stone when Babitz was twenty-seven years old. In an eerie twist of fate, the two died within a week of each other in December 2021. Collective mourning ensued in the literary world, honoring a severe loss for Babitz and Didion’s peers and contemporary fans alike. Most striking about the women’s voices is their shared ability to capture candid and visceral moments in cultural history as often as possible. Their respective writing styles are vastly different: Didion writes with a cool sense of intellect; her work is personable and intimate, with her academic background eloquently balanced with her strong desire to make sense of the world around her. Babitz’s work feels like reading a personal diary, her stories functioning as a written record of society, celebrity, and excess in Los Angeles.

While Didion valued introspection and Babitz valued social status, their unifying fascination with Los Angeles merged their efforts as writers. Both fixated on various figments of the city that captured their interests. One mutual preoccupation of theirs was Jim Morrison, the lead singer of California rock band The Doors. Morrison, as he is remembered, has become synonymous with the rock ‘n’ roll culture of Los Angeles. Since his untimely death in 1971, his posthumous memory has cultivated an aura of mystique that has pervaded popular culture in the decades that followed. Didion and Babitz’s writings on Jim Morrison are some of the few that reach beyond the myth surrounding his character, intimately examining who he was as a person. Their essays reside in the category of style as substance (Yagoda 16), as their voices elevate their narratives from the superficial to the deeply personal. Didion and Babitz reclaim literary journalism to craft their stories of Los Angeles in artfully distinctive ways, with the subject of Jim Morrison functioning as a compelling figure that represents the mystery of their home city.

Joan Didion’s contributions to literature and journalism speak for themselves. She is one of the most pivotal figures in American literary culture, and her narrative voice surely sets her apart from her contemporaries. Her famed essay “The White Album” opens the titular collection, first published in 1979; written over ten years, the essay captures history as it transpired in Los Angeles between the 1960s and early ‘70s. As Hilton Als expresses in the documentary Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold, “You couldn’t make a narrative about the times. The times weren’t cohesive. So, she found this way, which is to kind of make a verbal record of the times… The weirdness of America somehow got into this person’s bones and came out on the other side of a typewriter”(37:20-37:33, 38:17-38:21). She dedicates Part Three of “The White Album” to a day spent at the studio with The Doors in 1968. The first line immediately displays Didion’s clear attention to detail: “It was six, seven o’clock of an early spring evening in 1968 and I was sitting on the cold vinyl floor of a sound studio on Sunset Boulevard, watching a band called The Doors record a rhythm track”(25). Her description is so attentive that it makes the reader feel as though they, too, are seated on the cold vinyl floor, watching The Doors; her words draw one into the scene and go beyond surface-level reporting. To quote Tom Wolfe, Didion can be perceived as adopting a form of creative nonfiction, which “combined in-depth reporting with literary ambition: they wanted to make the nonfiction story shimmer ‘like a novel’ with the pleasures of detailed realism,” (Yagoda, quoting Wolfe, 17). In “The White Album,” Didion supersedes traditional rock journalism in favor of crafting a piece that investigates The Doors, in all their mysterious glory. She claims her space as both writer and fan, unashamed to express her admiration for the band’s music while doing so in a lucid way. Though she admits, “On the whole my attention was only minimally engaged by the preoccupations of rock-and-roll bands,” she openly conveys what she loved about this rock band, in particular:

“The Doors were different, The Doors interested me. The Doors seemed unconvinced that love was brotherhood and the Kama Sutra. The Doors’ music insisted that love was sex and sex was death and therein lay salvation. The Doors were the Norman Mailers of the Top Forty, missionaries of apocalyptic sex.”

Of all the legends that surround The Doors, as both musicians and as symbols, Didion precisely conveys the power behind the band’s message. First, she establishes her position as a non-avid fan of rock ‘n’ roll, occupying a unique space as a fan and granting herself increased credibility to write about The Doors objectively. She then takes into account the culture in which she found herself: the hippie counterculture that took over Los Angeles. Didion establishes that she and The Doors shared a mutual understanding: both parties came from academic backgrounds and were disillusioned by the turmoil they found themselves living in. Her resonance with the band is clear in her diction. She personifies their music as “insist[ing] that love was sex and sex was death and therein lay salvation,” a brilliant way to describe their lyrics that strives beyond mere analysis.

She likens the band members to religious figures, posing them as the “salvation” of rock ‘n’ roll and calling them “missionaries of apocalyptic sex.” Didion grants The Doors a great deal of power in her words, personifying their mission as a sexually-driven force in rock music. She describes Jim Morrison as “a 24-year-old graduate of U.C.L.A. [sic] who wore black vinyl pants and no underwear and tended to suggest some range of the possible just beyond a suicide pact,” (26). Capably describing the uniform Morrison often wore, Didion effectively implicates the layers of his character: he is educated, but dangerous; he is young and cynical, a product of his generation; he possesses sex appeal, but also a death wish. She goes on to utilize repetition to emphasize Morrison’s position as the ringleader of his band, repeating “It was Morrison” six consecutive times. A standout line reads, “It was Morrison who wrote most of The Doors’ lyrics, the peculiar character of which was to reflect either an ambiguous paranoia or a quite unambiguous insistence upon the love-death as the ultimate high.” This reveals the intricately woven aspects of Morrison’s image as the frontman: not only does he write the majority of the lyrics, but his “peculiar character” demands the reverence of his audience. Here, Didion asserts herself as a true literary journalist, reporting on Morrison while analyzing his character and crafting a narrative out of his theatrics. She writes that he projects “the idea”(27) behind The Doors, and she spends the remainder of the essay scrutinizing what exactly “the idea” could possibly entail.

A distinguishing factor in Didion’s essay is her use of dialogue. Yagoda describes the use of quotations as “antiliterary,”(14) arguing that “they take the reader away from the moment in question to some vague and indeterminate present in which the quote is uttered. They take the writer away from his or her voice.” However, Didion’s use of quotations elevates her story, revealing the inner dynamic of The Doors and the tensions felt in the room. While the line “they were gathered in uneasy symbiosis”(26) could have easily sufficed for her description of the band, she goes further in quoting the members directly in order to get a sense of their individual characters. A prime example follows as Jim Morrison finally arrives at the studio:

“The curious aspect of Morrison’s arrival was this: no one acknowledged it… An hour or so passed, and still no one had spoken to Morrison. Then Morrison spoke to Manzarek. He spoke almost in a whisper, as if he were wresting the words from behind some disabling aphasia.‘It’s an hour to West Covina,’ he said. ‘I was thinking maybe we should spend the night out there after we play.’ Manzarek put down the corkscrew. ‘Why?’ he said. ‘Instead of coming back.’ Manzarek shrugged. ‘We were planning to come back.’ ‘Well, I was thinking, we could rehearse out there.’ Manzarek said nothing. ‘We could get in a rehearsal, there’s a Holiday Inn next door.’ ‘We could do that,’ Manzarek said. ‘Or we could rehearse Sunday, in town.’ ‘I guess so.’ Morrison paused. ‘Will the place be ready to rehearse Sunday?’ Manzarek looked at him for a while. ‘No,’ he said then… I was unsure in whose favor the dialogue had been resolved, or if it had been resolved at all”(28-29).

Transcribing this scene shows Didion’s diligence as a writer and reporter, along with her ability to acknowledge the underlying significance of what she is witnessing. The use of quotations does not eliminate her voice as a writer, but rather enhances it and extends her initiative. Didion fixated on The Doors because, in her words, they were “different.” She understood, subconsciously, that the exchange between Morrison and Manzarek was not a simple conversation, but one that was marred with mutual tension and ambivalence. Capturing this dialogue revealed a layer to The Doors’ dynamic that was not often explored, peeling back the myth of the “rockstar image” and exposing the truth: two people trapped by their fame, barely able to communicate effectively with one another. Didion’s insertion of her thoughts re-emphasizes this: “I was unsure in whose favor the dialogue had been resolved, or if it had been resolved at all.” This experimentation with dialogue proves Didion’s investment in her subject: in her pursuit of the truth, she seeks to be both precise and inquisitive. She admits that while she may not hold all of the answers, she can sense that something crucial has taken place.

The scene closes with Didion’s vision of Morrison: “Morrison sat down again on the leather couch and leaned back. He lit a match. He studied the flame awhile and then very slowly, very deliberately, lowered it to the fly of his black vinyl pants. Manzarek watched him”(29-30). Ever-so observant, Didion manages to seize the perfect moment in which Morrison lives up to his daredevil, rockstar-cliché persona. Her attention to detail places her in an almost trance-like state, as though she could not help but watch Morrison do something so reckless and out of the ordinary. Yet, to see his bandmate so unfazed by what is occurring shows the divide between journalist and artist: Didion is unaccustomed to Morrison’s theatrics, initially only understanding from an outside perspective. Her analysis of Morrison successfully humanizes him, assessing his character with an intricacy that combines rock journalism and critical analysis in a persuasive way.

Eve Babitz, the “hedonist with a notebook”(Green) was a criminally underrated writer, more often remembered for her “party girl” image and her role as a muse to many Hollywood greats. Her prose, like Didion’s, can be viewed as creative nonfiction, her novels often fictionalized versions of real-life events. What was enthralling about Babitz was her unwavering pursuit of pleasure. She was shameless in her love of glamour and excess, a true hedonist living in a bohemia of her creation. In her first published book, Eve’s Hollywood, she includes Joan Didion and her husband, John Gregory-Dunne in her acknowledgments: “to the Didion-Dunnes, for having to be what I’m not”(xx). Much can be said about Babitz, but her self-awareness is of no question. She was not accepted by the intellectual writers of her day and did not hope to be—more than anything, she wrote for herself and in honor of the city of Los Angeles. Her writings, which were consistent over three decades, remained largely forgotten in the literary world, with Babitz often not being taken seriously and overshadowed by her peers—Didion included. Yet, her work had its own renaissance thanks to Lili Anolik, who profiled Babitz for Vanity Fair in 2014; this led to reprints of her books, as well as a new collection of works, I Used to Be Charming (2019). This anthology features pieces written over two decades for various publications and reveals a more vulnerable side to Babitz that she did not often show.

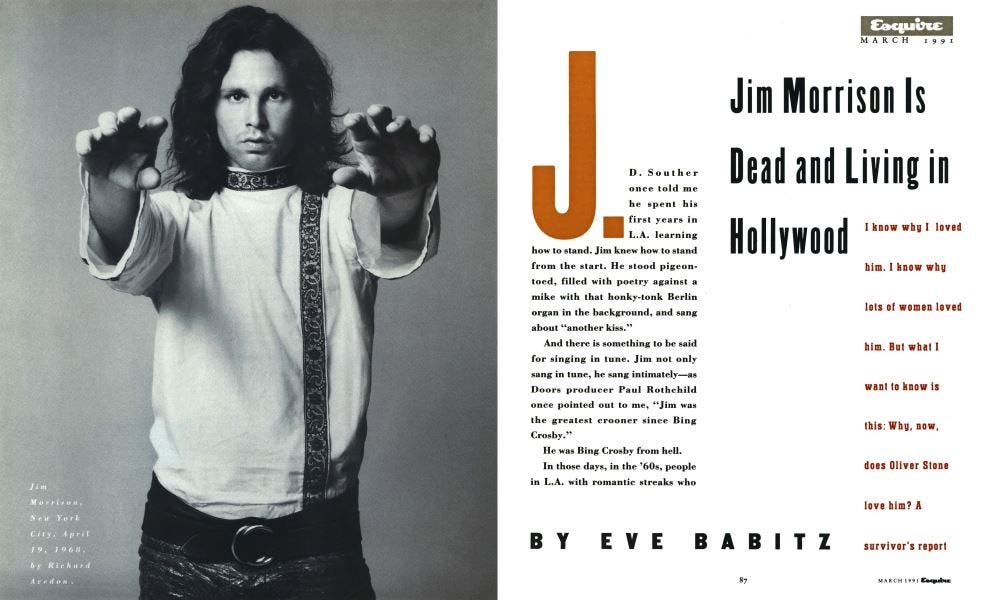

The piece “Jim Morrison Is Dead and Living in Hollywood” first appeared in Esquire magazine in March 1991, twenty years after his death. Famously, Babitz and Morrison had a romantic relationship, which began prior to The Doors’ success and continued sporadically for several years. Knowing this context promptly sets Babitz apart from nearly every writer who has profiled Morrison: she is not writing as a fan, nor as a music journalist, but as a friend and lover. Further, she wrote this piece as a posthumous homage to Morrison, which differs from Didion, who was profiling the artist in real-time. Thus, Babitz’s writing is brazenly critical; she does not strive to sugarcoat her memories of Morrison but rather bluntly lays out her feelings on the page. She recollects The Doors by writing, “Rock groups who went to college and actually got degrees were not only uncool, they were unheard-of… The Doors were embarrassing, like their name. I dragged Jim into bed before they’d decided on the name and tried to dissuade him; it was so corny naming yourself after something Aldous Huxley wrote”(221-222). Babitz saw through the aura of elitism Morrison and The Doors attempted to contrive for themselves, knowing enough about the artist mentality to not be persuaded by their image. Her candor is striking; it is almost as though, after growing up surrounded by famous figures, Babitz is disillusioned by the concept of “celebrity” and therefore unafraid to speak her mind about one who is so revered by his fans.

She writes of the first time she met Morrison: “I met Jim early in ‘66, when he’d just lost the weight and wore a suit made of gray suede, lashed together at the seams with lanyards, and no shirt. It was the best outfit he ever had, and he was so cute that no woman was safe”(223). Babitz holds similar attention to detail as Didion, in that she notes the intricacies of Morrison’s appearance even decades after the occurrence. Yet, this further shows the genuine importance Babitz places on such details: she is not just noting the color and material of Morrison’s shirt out of sheer memory; she describes the clothing because she prescribed Morrison’s appearance to his character, and subsequently, his reputation. Babitz was unapologetically shallow; she paid attention to the perceived attributes of everyone she encountered because she felt that, in a city like Los Angeles, a charismatic appearance was paramount.

Babitz then tackles Morrison’s image as it came to be regarded by his fanbase. “Jim as a sex object and the Doors as a group were two entirely different stories. The whole audience would put up with long, tortured silences and humiliation… [Jim] could get away with it because his audience was all college kids who thought the Doors were cool... Jim as a sex object lasted for about two years… he became more of a death object than a sex object. Which was even sexier”(225). Here, Babitz dissects the artist-versus-fan dynamic. Morrison as a so-called sex object claims ownership of his audience’s adoration—but only for a short time. Once his perception turns from sexual to ghastly, he is no longer as desirable. Babitz, though, continues to see the appeal that goes beyond The Doors’ music. She recognizes the star quality that Morrison once possessed, and she writes about him with a sense of morbid fascination. Her voice is both fanatic and nonchalant, and this duality makes for an intriguing narrative. She proceeds with her mournful tone as she positions Morrison within the complicated world of Los Angeles:

“But as long as Jim was on foot in L.A.—as long as he was signed to Elektra and in a world where if he fell, it would be into the arms of emergency rooms or girls who knew and loved him—he was, if not OK, at least not dead. There was always somebody around who would break down the door. He could never get away with killing himself in L.A.”(229).

Babitz’s musings on death continue for the remainder of the essay, as she poses questions such as, “But what does that mean—death, the way it sounds?”(232). She is fixated on dissecting the subconscious truth behind Morrison’s passing. Was he a victim of Los Angeles, of fame and excess? Did his addictions finally catch up to him? Did he take his own life? Babitz seems to only remember what she distinguished him as, the sex-death object that she fell in love with. She calls Los Angeles a wasteland on multiple occasions and seems to hold a similar sentiment in this piece. It is as though she does not want to believe that someone she put her faith in would disappoint her so deeply, seeking to place the blame on anyone, anything, but him. Thus, she indicts Los Angeles as the primary cause behind Morrison’s demise, a city pervaded by obsessive fans, record labels, and trusted others who wanted to make Morrison into someone he was not. Interestingly, Babitz never directly addresses her reaction to his death, only her theories and underlying distress.

Babitz finds herself stuck in the memory of who Jim Morrison once was, almost unwilling to fully accept his death. She writes, “I began running into women who kept Jim alive–as did I—because something about him began seeming great compared with everything else that was going on”(232). The piece turns from a straightforward criticism of The Doors to a mournful remembrance of what once was. This unique structure allows Babitz to display a rare showcase of vulnerability, whose writing often focused more on indulging her hedonistic tendencies. Her words merge her self-indulgence with genuine sympathies. The reader can sense her emotional investment in her subject, not solely because of her intimate connection with Morrison, but because she shows an understanding of the loss that his death created for the culture of Los Angeles, and the music world at large.

Didion and Babitz possess a commonality in Morrison, who represents, for the both of them, something different to come out of Los Angeles. While Didion dissects him from afar, Babitz inspects their connection and appears on the other side just as unsure as she was before. Lili Anolik writes, “[Didion and Babitz are] writing about L.A. at the exact same time with a totally different vision of what Los Angeles is, and I think you need both of them. In many ways they’re yin to the others’ yang”(Vanity Fair, 2014). The two women were plagued by the culture surrounding them and a mission to make sense of the changes they were witnessing. The beauty of their connection lies in their ability to coexist while living radically opposite lifestyles, and in their shared passion for writing about their environment in ways that were deeply personal to them. Both women harnessed a form of intellect that was chic, with a vague level of humility, and their contributions to literary journalism will surely withstand every cultural shift to come.

References:

Anolik, Lili. “All About Eve — and Then Some.” Vanity Fair, 14 February 2014,

https://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2014/03/eve-babitz-los-angeles-party-scene. Accessed 7 April 2022.

Appleford, Steve, and Michael Walker. "Eve Babitz’s Hollywood Ending." Los Angeles

Magazine, vol. 67, no. 4, Apr. 2022, pp. 64+. Gale General OneFile, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A699679997/ITOF?u=ecl_main&sid=ebsco&xid=9af05d85. Accessed 17 Apr. 2022.

Babitz, Eve. “Jim Morrison is Dead and Living in Hollywood,” I Used to Be Charming, New York Review of Books, 2019.

————. Eve’s Hollywood, New York Review of Books, 2015.

Didion, Joan. “The White Album, 3,” The White Album, eBook, Farrar, Strous, and Giroux, 2009.

Green, Penelope. “Eve Babitz, a Hedonist With a Notebook, Is Dead at 78.” The New York Times, 19 December 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/19/obituaries/eve-babitz-dead.html/ Accessed 7 April 2022.

Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold. Directed by Griffin Dunne, performance by Joan Didion and Hilton Als, Netflix, 2017.

Pierce, Barry. “The death of the ‘chic’ writer,” Dazed Digital, 9 February 2022, https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/55411/1/the-death-of-the-chic-writer. Accessed 16 April 2022.

Rivieccio, Genna. “‘Is That the Blue You’re Using?’: Eve Babitz and the Undermining of the ‘Didion Approach’ to California.” The Opiate, 19 December 2021, https://theopiatemagazine.com/2021/12/19/is-that-the-blue-youre-using-eve-babitz-and-the-undermining-of-the-didion-approach-to-california/. Accessed 18 April 2022.

Yagoda, Ben. “Preface,” & “Making Facts Dance,” The Art of Fact: A Historical Anthology of Literary Journalism, Scribner, 1997, pp. 13-20.

Love this piece on my fav literary cool girls